THE STONE BALLS OF COSTA RICA ... YET ANOTHER OPEN AIR UNIVERSITY FOR TEACHING PRINCIPLES OF NAVIGATION.

During the past 65-years there has been considerable commentary about the "Stone Balls" of Costa Rica, but very little hard analysis leading to some understanding of what they could have been used for. Early 20th century archaeologists like Doris Stone and Samuel Lothrop investigated a number of sites and left us with a partial record of where some of the huge and smaller spheres were sitting "in situ", as well as the widely variable dimensions of carefully measured stones. Were it not for their pioneering work, it's doubtful that there would be any chance whatsoever of seriously addressing the question of "function", based upon "position", as most of the stones have now been taken away to serve in a new capacity as "garden ornaments". As it stands, it's now the 11th hour for these archaeological wonders, and unless some major analysis and serious scientific work is undertaken in the next few years before the last of the old-timers of the Diquis Delta die off, then we will have no hope of knowing the exact positions where the stones formerly resided and that knowledge is absolutely imperative to any understanding of their purpose. Lothrop observed after his 1948 expedition:

Almost every archaeological site in the farming areas of the Diquis Delta is known to the individuals who have prepared the land for planting or have taken part in the cultivation and harvesting. At the outset, forest growth had to be cut down and burned. Roads and drainage ditches then were constructed; intricate pipe lines for overhead irrigation and for spraying were laid down; leveling by bulldozer was carried out wherever needed. At this stage of development, all such features as stone balls or house mounds were clearly visible (See: Archaeology of the Diquis Delta, Costa Rica pg. 117).

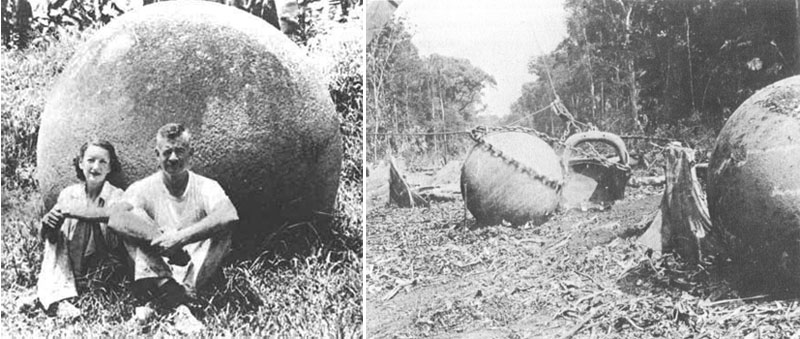

Archaeologist Samuel Lothrop pictured with his wife Eleanor during their investigation of sites in the Disquis Delta in 1948. Earlier (1943), Archaeologist Doris Z. Stone photographed these round stones being shifted during jungle clearing to make way for railway tracks that would service the United Fruit Company banana plantations.

A lot of this preliminary land clearing and ground preparation took place in the 1940's and there will yet be a few "old-timers" who can remember the exact positions where the balls originally sat "in situ", either on mounds or elsewhere on the natural landscape. Let's, therefore, ask them to point out these spots and get exact GPS readings. We need also to know precisely which individual stones sat at which positions and their measured size, as well as where all of the "appropriated", migratory stones ended up.

In this present study we'll go back to basics and put the stones "electronically" into the landscape to the best of our ability, using the all-too-sparse archaeological record as our guide. This process of restoration will need to be done over time, as more information comes to light concering precise GPS positions of former component round stones, statues and the marker mounds upon which they sat.

THE DIQUIS DELTA ... Home to the majority of the stones.

The Diquis Delta is a rich farming district adjacent to the

Pacific Coast of Costa Rica (which in Spanish translates to "rich coast").

For ancient, shallow draft ships approaching from the open sea there appears

to have been ample opportunity to find safe havens within the several coastal

estuaries and waterways or within the large harbour mouth southeast, which

offered shelter from the open sea storms behind the Peninsula de Osa. The

many waterways emptying into the Pacific extended far inland and offered extensive

navigable passage for small boats.

The country itself was only 75-miles wide through the isthmus, making it an

appealing transit location for human traffic and cargos moving between the

Atlantic Ocean and Pacific coast. Geographically, this stretch from Costa

Rica to Panama was the only natural or practical crossover point for intercontinental

migrants from the Mediterranean or Pacific countries and this attribute, supported

by archaeological and flora evidence, suggests that the region was a hub of

ancient maritime activity on both coastlines. For example: The coconut, which

serves as a major staple food source throughout the Pacific, seems to have

been introduced to the many Pacific countries and islands from a point of

origin in the environs of Costa Rica. Heyerdahl writes:

'... there is nothing in the Polynesian traditional

history to indicate that the coconut was found growing wild locally when the

aboriginal Polynesian discoverers arrived. Hawaiian history claims that the

coconut was introduced to their islands from Kahiki by two seafaring

brothers Ipua and Aukalenuiaku. (Forander 1919). Polynesian settlements west

of the Marquesas Group are full of legends of an early period when there were

no coconut palms on the islands. Some, like the Tahitians, resort to fables

or allegories to account for the introduction of the species, but others,

like the natives of Manihiki and Rakahanga state plainly that on their own

islands "there were no coconuts, nothing but a bare plain", until

visitors from Rarotonga came and planted coconuts, which they had carried

along. (Gill 1915, p. 146).

In Melanesia the coconut certainly does not seem to be of very great antiquity,

according to native memories and beliefs. Riesenfeld (1950 b), throughout

his exhaustive study of Melanesian lore, shows that the coconut is recollected

independently in different parts as a food brought to the islands in fairly

recent times, often by legendary heroes of "light skin". ...'

The latest comments on the subject come from Sauer (1950 p. 524), who lists

the coconut among cultivated fruits and nuts of prehistoric America. He says:

"Probably only two palms in the New World were truly domesticated in

aboriginal culture, the coconut and pejibaye. The others appear to be unmodified

wild species,..." Stating that we have "adequate and explicit"

eyewitness evidence that the coconut palm was already established "in

great groves in Panama, Costa Rica, and on Cocos Island" when the first

Spaniards arrived, he adds: "It is possible that such groves of coconuts

existed as far north as the coast of Jalisco (On the latitude of Mexico City.)

Further: "The earliest known groves in the New World were in part along

the coast and in part some distance inland, but then, as now, apparently always

as groves, and not scattered through the native jungle or brush." (See:

American Indians In The Pacific, pg. 464).

Lothrop writes concerning stone statues found in the Diquis Delta:

'Heads are of several distinct types. They may be circular

(pl. VIII, e) semicircular (pl. VIII, g), oval (pl. VIII, c), or greatly elongated

(pl. IX, e). Most of them appear to be bald, but some wear caps (pl. IX a,

c, e) and others have hair hanging down the back, cut off square below the

shoulders (pl. VIII, b). The caps are found usually on male figures and the

long hair on women. This distinction is true of all specimens we illustrate

but Mason (1945) has published some Diquis exceptions. In his Las Mercedes

series many women are shown with caps.

Plate VIII c, illustrates a head with what appears to be a beard. Facial hair

normally was sparse throughout the New World, but beards definitely existed.

For example, they are represented in Mexican and Mayan art (Vaillant, 1931;

1935, pp. 48, 54, 60, 61) and are typical in Peru on trophy head effigy jars

of Nazca style (Gayton and Kroeber, 1927, pl. 7, B, D, E).

A number of researchers have commented about the style shown in certain of the South American caps depicted on statuettes as being very reminiscent of the typical maritime caps worn by Phoenician sailors from the Mediterranean. That large populations of bearded Europeans once inhabited vast areas of South America is attested by the physical anthropology of tens of thousands of perfectly preserved mummies, as well as innumerable statues, wall reliefs, artefacts, etc., showing distinctly European physiology. This regional truth is, however, very unpopular and does not suit the agenda of the overseer PC regime that controls what is presented to the world as "history". Where any evidence is found to indicate an ancient European presence in the Americas or Pacific, as elsewhere outside of Europe itself, that knowledge is muted and goes unmentioned, no matter how dynamic and compelling. The fact is that the highly mobilised European cousin nations built long enduring civilisations on many ancient continents, which lasted until invaders or camp followers annihilated them, then later laid claim to any remnant structures, artefacts or cultural symbolism left behind. To openly state this incontestable fact means career suicide to any mainstream archaeologist or physical-anthropologist foolhardy enough to publish honest assessments of findings.

The evidence shows that the extended isthmus between Costa Rica

and Panama was, anciently, a major port of call for ships and crossover point

for two-way traffic, ranging between Europe and the Mediterranean and across

the vastness of the Pacific. Costa Rica represented the doorway (Puerto or

Porte) between regions. Because of this condition, it was imperative that

a major "School of Learning" exist within the isthmus to supply

well-trained navigators to the ocean traversal incentives being undertaken

from coastlines on each side of the country.

Beyond the huge, sprawling desert school at Nazca Peru, there was yet this

other school situated in the very verdant and wet terrain of the Diquis Delta,

Costa Rica. Let's now electronically reconstruct as much of the school as

the archaeological record allows and see how it worked in teaching initiates

the principles of ancient navigation shared and taught by the worldwide distribution

of cousin European nations.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF DORIS STONE & SAMUEL LOTHROP

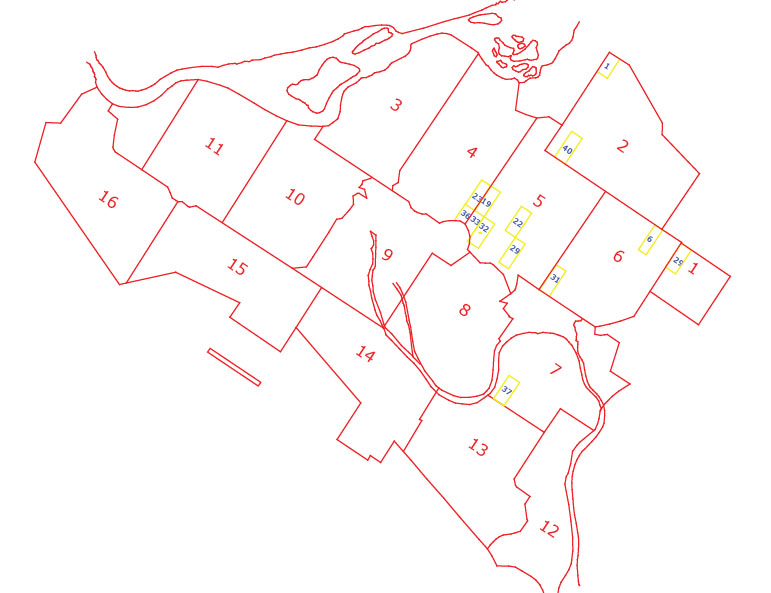

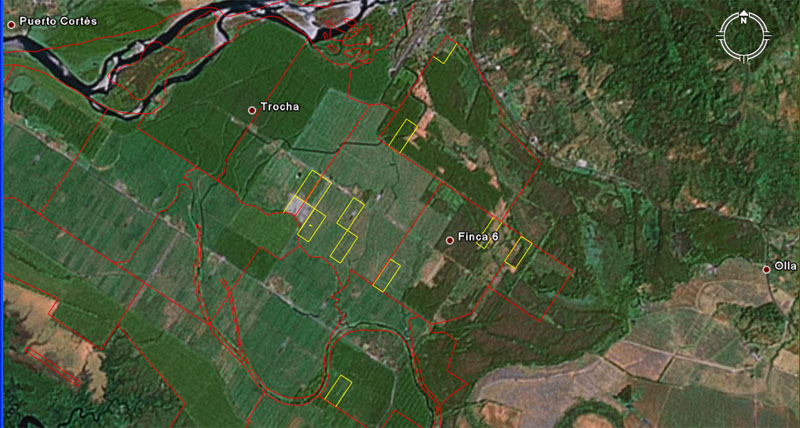

The layout of farms where Stone and Lothrop worked in the 1940's. The yellow rectangles indicate the sections within the farms where they did archaeological digs or recorded stone ball alignments and measured the size of individual stones. (Map copied from: 1993 Investigaciones Arqueológicas en el Delta del Diquís, by C. F. Baudez, N. Borgnino, S. Laligant and V. Lauthelin, Fig. 6, pg. 28). The authors state that these were the sections visited by Lothrop.

Here are the plots where investigations were carried out, superimposed over the Diquis Delta landscape. We can now describe more adequately and clearly what was recorded to be archaeologically present on each farm section during the 1940's. There are also surviving round stones at the location named on the Google Earth image as "Finca 6" and yet more at the location to the extreme right named "Olla".

Many parts of the Diquis (meaning "large water")

Delta would be classified as a semi-wetland or certainly as a flood-plain,

which was sometimes fed by such a confluence of mountain runoff that the water

periodically spilled over the river banks and inundated the flatlands. Although

this occurrence is nowadays held in check by numerous drainage ditches, it

was once quite frequent. Despite this, archaeological evidence indicates that

the rich land of the Diquis Delta was under permanent cultivation by many

generations of people over a very long period of time.

The ever-present threat of flooding meant that the permanent structures had

to be placed on raised mounds or platforms, many or most of which sat a minimum

of 5-feet above ground level and were stone-lined or walled around the perimeter

to arrest water erosion effects. Along with these "sometimes-island"

mounds built purely for domestic dwellings and human occupation were yet others

upon which the large, carefully carved, spherical boulders or stone statues

were placed. Yet other spherical boulders sat in alignments at ground level,

presumably on terrain elevated enough to be less susceptible to the periodic

encroachment of floodwaters. In terms of the count of these laboriously hand

hewn and shaped stones, Lothrop states:

'It will never be possible to secure an exact count of the stone balls. Many have been removed to adorn parks and gardens. Others have been blasted to bits owing to the native belief that they contain gold. Certainly, they numbered many hundreds if not thousands. Sometimes they occur singly, sometimes in groups. The largest group I have heard of contained at least 45 balls according to Dr. Paul Allen. We observed a total of sixty-odd in their original location at 14 sites (table I). Of these, 2 sites had 7 balls each, 2 sites had 6, and 3 sites had 5 (figs. 3, 4).

Here's Lothrop's list of balls seen (by him or other reliable witness's) "in situ":

Number |

Location |

Remarks |

7 |

Farm 2. Sec. 40 |

Pl. VII, a; fig. 72 |

7 |

Farm 4, Sec. 32 |

Fig. 3 |

6 |

Farm 4, Sec. 36, Site C |

Pl. VI, b-ce; fig. 4 |

6 |

Farm 6, W. end |

|

5 |

Farm 1, Sec. 29 |

Pl. VII, d |

5 |

Farm 4, Sec. 23, Site A |

Fig. 6 |

5 |

Farm 4, Sec. 23, Site F |

Fig. 6 |

3 |

Farm 4, Sec. 23, Site B |

Pl. VII, c |

2 |

Farm 6, E. end |

|

1 |

Farm 4, Sec. 36, Site G |

Fig. 71 |

1 |

Farm 5, Sec. 19 |

|

1 |

Farm 5, Piedra Partida |

|

1 |

Farm 7 |

Pl. I, bottom |

Lothrop also provides a list of "Other" round stones.

Number |

Location |

Remarks |

ca. 45 |

Jalaca (R.R.-K. 60) |

Information from Paul Allen |

15+ |

Piedras Blancas, Ovando Farm |

Information from Paul Allen |

17+ |

Ilsa Camarones |

Pl. VI, a. Not all in situ |

10 |

Farm 7 |

Stone, 1954, p.7 |

ca. 10 |

Palmar Sur - scattered |

Not in situ |

7 |

Farm 16 |

Not in situ |

5 |

Farm 5, mandador's house |

Not in situ. Some from Farm 5, Sec. 32 |

5 |

Cerro Zapotal |

Information from Doris Z. Stone |

? |

Farm 5, Sec. 34, S. of canal |

|

3 |

Palmar Norte Plaza |

Not in situ |

2 |

Farm 15 |

Not in situ |

2+ |

Webb Farm behind Puerto Cortes |

Two are over 8 ft. diameter |

? |

North of Puerto Cortes |

Information from Jaime Anderson |

2 |

Moved to Golfito |

Not in situ |

6 |

Moved to San José de Costa Rica |

Information from Doris Z. Stone |

2 |

Cavagra |

Information from Doris Z. Stone |

1 |

Peabody Museum, Harvard |

Small specimen from Farm 2 |

1 |

Farm 2 Sec. 40 |

Private collection. Pl. V |

3 |

American Museum of Natural History, New York |

Keith collection |

All-in-all, the ancient people went to great effort to set up this expansive system of marker mounds, with arrays of round stones or statues adorning their tops or set out in geometric patterns and alignments across the landscape. The system was spread over many square miles and incorporated hundreds of huge and smaller round boulders, most of which had been very precisely carved out of incredibly hard granodiorite, which Lothrop describes as a "local lava". He also rated the density of this stone as "3.0" on the scale of hardness and states, 'Hence their weight [stone balls] runs from a few pounds to 16+ tons (ca. 15,000 kg.).