THE WINTER SOLSTICE FOR NEW ZEALAND, JUNE 22ND 2023.

For the June 22nd winter solstice we decided to head for Raglan, on the North Island of New Zealand's west coast and test the merits of one of the many ancient "solar observatories" still surviving there. These structures were erected by the people who lived in New Zealand before the arrival of the Polynesian-Melanesian Maori people from Eastern Polynesia around 1300 AD and still function very accurately for determining the precise dates of the equinoxes and solstices.

The Patu-paiarehe and other early inhabitants that are identified under that umbrella term (Turehu, Waitaha, etc.) were adept astronomers and surveyors, who maintained very accurate calendar systems. For continued accuracy, year-by-year, over thousands of years, they erected solar observatories in all the locations where sizable communities dwelt across the length & breadth of New Zealand.

These solar observatory locations generally included a wide assembly area where seasonal festivals, celebrating the changing of the seasons, took place. Whereas the learned astronomer-surveyor would occupy the finite observation position at the carefully erected marker (obelisk-boulder, mound-hump or sighting-pit) to determine whether or not the exact day of an equinox or solstice had been reached, the rank & file of local society, gathered-in, could also watch the brilliantly illuminated, milestone spectacle of solar rise or set.

The Raglan area, especially locations to the Northeast, East and Southeast of the seaward coast's Karioi Mountain, provides a rich abundance of solar observatories that used the peaks and summit trough positions as the outer marker for fixes onto the descending and alighting solstice or equinox sun.

Mount Karioi on New Zealand's west coast at Raglan. It was the most commonly used outer-marker target for equinox (autumnal or vernal) or solstice (summer or winter) fixes, by the ancient Patu-paiarehe people, from their solar observatories in the region.

The mountain was also an ancient, extinct volcano and one of the ages-old traditions of the Patu-paiarehe people was to "return fire to the volcano", using the fiery glowing orb of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes to settle into the cone or crater (sunset) or ascend therefrom (sunrise). This pre-occupation was based upon giving honour to their god of thunder and lightening, who was "appeased by fire, bright flashes and loud claps of thunder".

In the Northern Hemisphere, from whence distant ancestors of the Patu-paiarehe came, that god was called Taranis (ancient Gaul) or Taranaich (ancient Scotland), but in New Zealand called Taranaki or Tawhaki.

At a distance of 107-miles (172 kilometres) further down the west coast and viewable from Mount Karioi on clear days, is dormant volcano Mount Taranaki. This sometimes active volcano, with its bright flashes, loud clap explosions and fiery spewing lava has many solar observatories standing away from it.

Mount Taranaki bathes in the late afternoon sun in the background. In the foreground is a flat-topped, specially built mound structure to act as a solar observatory for witnessing the equinoctial sunrise, where the morning sun climbs up the southern side of the mountain to launch itself into the sky at the peak. Note the two large boulders placed at each side of the observatory platform.

Equinoctial sunrise as observed from the Patu-paiarehe altar-platform at Rahotu, South Taranaki. Many more similar solar observatory structures survive in the district.

From atop the platform, "first glint" of the equinoctial sun was observed at the southern base of Mount Taranaki, where the inclined mountain slope conjuncted with hill terrain at the base (forming a "V"). The sun then climbed the mountain to sit above the crater at the peak, leaving a sun glow down the side reminiscent of glowing, molten lava. Mount Taranaki, in both name and attributes of a sometimes active volcano, epitomised the thunder and lightening god Taranis-Taranaich of the Northern Hemisphere.

This mountain-climbing modus operandi is used frequently at Patu-paiarehe solar observatories and provides the observer with more time to get an accurate fix, when cloud cover intermittently obscures the view. Ancient sunrise observatories at Taupo (using Mount Maunganamu as the outer marker) or Maunganui Bluff, Northland (using Mount Tutamoe's sharp face as the outer marker) work in this same manner.

RAGLAN'S BRIDAL VEIL FALLS AND PIRONGA MOUNTAIN, HOME OF ANCIENT PATU-PAIAREHE TRIBES

East-south-east of Raglan's Mount Karioi is a large bush-clad native reserve called Waireinga (water path to the underworld). In Maori oral history it is well-recorded that this region, as well as Mount Pirongia (further east-south-east) were some of the last haunts or sanctuaries of the Patu-paiarehe, who were besieged, enslaved, cannibalized and finally annihilated by the fierce Maori warriors.

A drone image taken at the winter solstice, viewing over the western-most ridge of bush-clad Waireinga Reserve to looming and majestic Mount Pirongia on the distant horizon. Pirongia mountain covers a vast area and generations of besieged Patu-paiarehe, driven from their home territories, hid and found sanctuary there for years, up until recent centuries.

Behind the ridge in the foreground is the valley containing Bridal Veil Falls. This ridge obscured the view to Mount Karioi from the falls themselves, but was a relatively short walk from the cascading waterfall.

NGONGOTAHA MOUNTAIN TRAGEDY ... ANOTHER LOST HOME.

THE PATU-PAIAREHE TRIBE OF NGONGOTAHA

'The partly wooded mountain Ngongotaha, rising above the south-west shore of Lake Rotorua, was the principal haunt of the Patu-paiarehe people in Rotorua country. The fairy pa was at the Tuahu-o-te-Atua, on the summit of the mountain, and there were also fairy villages on the neighbouring range called Te Raho-o-te-Rangipiere, and at Whakaeke-tahuna, an earthwork-defended pa at the foot of the mountain on the northern side, near the Waiteti stream. The old man Tohe-te-Matehaere, of Weriwerei, Waiteti, whose hapu of the Arawa is Ngati-Ihenga, speaks as follows on the subject of these fairy mountain-dwellers:-

“The name of the tribe of Patu-Paiarehe at Ngongotaha and other places in this neighbourhood was Ngati-Rua, and the chiefs of that tribe, in the days of my ancestor Ihenga, were Tuehu, Te Rangi-tamai, Tongakohu, and Rotokohu. The people were very numerous;

There were a thousand or perhaps many more on Ngongotaha. They were an iwi atua (a god-like race, a people of supernatural powers). In appearance some of them were very much like the Maori people of to-day; others resembled the pakeha (or white) race. The complexion of most of them was kiri puwhero (reddish skin), and their hair had the red or golden tinge which we call uru-kehu. Some had black eyes, some blue like fair-skinned Europeans. They were about the same height as ourselves. Some of their women were very beautiful, very fair of complexion, with shining fair hair. They wore chiefly the flax garment called pekerangi, dyed a red colour; they also wore the rough mats pora and pureke. In disposition they were peaceful; they were not a war-loving, angry people. Their food consisted of the products of the forest, and they also came down to this lake Rotorua to catch inanga (whitebait).

From Taua Tutanekai Haerehuka and his wife, Huhia, who live at Wai-o-Whiro, a stream that issues from the northern base of Ngongotaha, comes this poetic legend of the same Patu-paiarehe community:-

“When the Maoris many generations ago set fire to the fern and forest on the slopes of Ngongotaha and destroyed much of the vegetation even up to the borders of Te Tuaha-o-te-Atua, there were great lamentations among the fairy tribe, and they wept for their mountain devastated by the fires of the strangers. Most of them departed from their ancient haunts and migrated northward to Pirongia and to Moehau (Cape Colville), on the persuasion of the chief Rotokohu. This song of farewell was chanted by the other Principal chief, Tongakohu, before he left his beloved mountain forever :-

(Translation.)

E muri ahiahi Night’s shadows fall;

Ka hara mai te aroha Keen sorrow eats my heart,

Ka Ngau I ahau, Grief for the land I’m leaving

Ki tuku urunga tapu, For my sacred sleeping-place,

Ka mahue I ahau The home-pillow I’m leaving,

I Ngongo’ maunga On Ngongo’s lofty peak,

Ka tu kau noa ra. So lone my mountain stands

Te Ahi-a-Mahuika Swept by the flames of Mahuika,

Nana I tahu mai-I I’m going far away,

Ka haere ai au ki Moehau To the heights of Moehau, to Pirongia,

Ki Pirongia ra e, To seek another home.

I te urunga tapu -e. O Rotokohu, leave me yet awhile,

E Te Rotokohu e! Let me farewell my forest shrine,

Ki ata akiaki kia mihi ake au The tuahu I’m leaving.

Ki taku tuahu ka mahue iho nei. Give me but one more day;

He ra Kotahi hoki e, Just one more day and then I’ll go,

E noho I au; And I’ll return no more!'

Ka haere atu ai e,

Kaore e hoki mai,

Na-a-i !

See: "The Patu-paiarehe. Notes on Maori folk-tales of the fairy people. Part II, by James Cowan, p 142-151"

In the 19th century, after New Zealand became a British colony, many abandoned remnant houses, like this one, were seen to be in an advanced state of deterioration on Ngongotaha Mountain. This one is found at Auckland War Memorial Museum.

METHOD FOR FINDING THE LOST OBSERVATION POSITION FOR THE BRIDAL VEIL FALLS (WAIREINGA RESERVE) PATUPAIAREHE COMMUNITY.

It is openly acknowledged in Maori oral history that the original inhabitants of Bridal Veil Falls were the Patu-paiarehe people. Given that this is the case, it is obligatory that they would have established a solar observatory there or somewhere nearby. What needed to be established was: What kind of solar observation did the location best lend itself to ... summer solstice, equinoxes, winter solstice, sun-rises or sun-sets?

As it turns out the frontal ridge, facing towards Mt Karioi, was in an excellent orientation to provide a marker to fix upon the winter solstice sunset, as the descending & alighting solar orb skimmed the mountain's northern peak, settled into the summit trough and melded-into the southern peak.

So, to find the marker where the observer needed be, in order to witness the exact day of the winter solstice, some back-engineering calculations needed to be done.

Using Google Earth, the distance and estimated angle were determined, taking into account that the sun would disappear early behind the high mountain, several degrees short of where it would finally disappear beneath the sea horizon. We then did a trigonometric calculation, based upon the elevation where the observer needed to be, the height of the mountain at the extreme summit and the distance between the two points on a flat plane. Beyond that the upwards angle to the mountain summit was calculated.

With these figures in hand we opened up Red Shift Astronomy program, put in the coordinates of the closely estimated observer's position at the Bridal Veil Falls ridge and the date of the winter solstice 2023 for New Zealand. We then set the horizon-line at the height of Mt Karioi's extreme summit. Next we chose the descending sun as our target and followed it down in the animated display till it touched the horizon line ... et voila! ... we now knew with excellent relative accuracy where the observation obelisk, mound or sighting pit should be found, if it had survived the rigors of time.

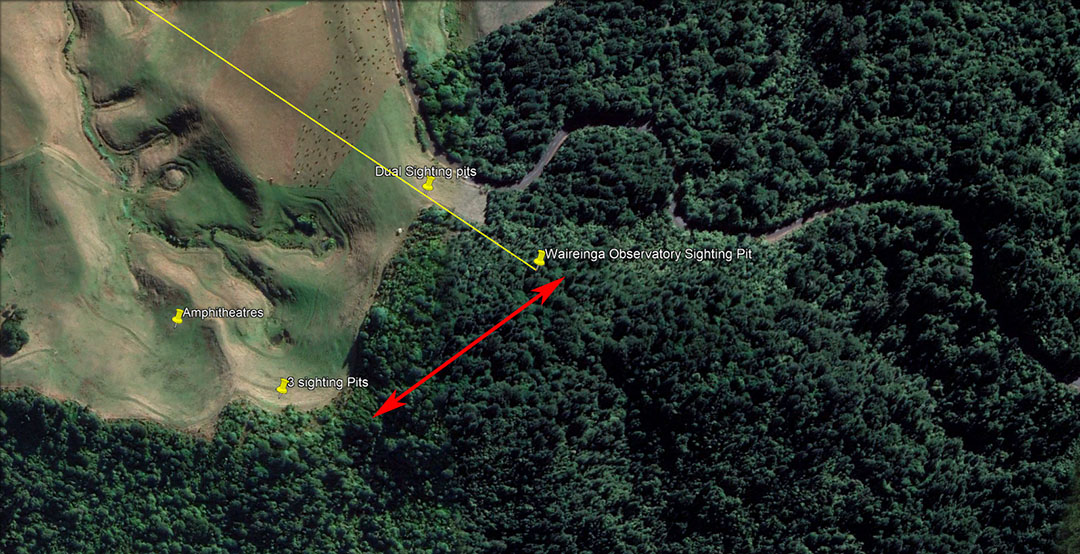

In an exploration of the bush-clad ridge we came across an anciently dug sighting pit, situated at the highest point and in the correct relative position. It was full of detritus, with trees growing to its sides after centuries of abandonment. It was not a water-course washout, nor was it the result of wild pigs rutting the ground. On the ridge plateau it was quite a unique feature. We found two more, side-by-side sighting pits on the same alignment further down at the edge of the bush and initially thought this second set oriented towards Magic Mountain over towards Te Mata.

We are very familiar with "sighting pits", having encountered and assessed hundreds of them at many ancient occupation-sites across New Zealand, where thousands of these pits have survived perfectly intact and recognisable as purpose-built structures. Our archaeologists erroneously categories them as "kumera-pits", for storing sweet potatoes. The pits had various uses, such as surveying alignments, astronomical observations (as in this case) or sentinel positions. They afforded the occupiers the chance to seat themselves low below the wind-line for added comfort during a long observation vigil.

THE WINTER SOLSTICE SPECTACLE

The late afternoon sun is still high in the sky.

Poised ready to descend.

On target.

Getting close.

Lining up.

Skimming the North peak.

Heading for the saddle.

Almost there.

In the saddle.

Fire restored to the volcano.

Afterglow.

Goodnight!... Repeat performance a year from now.

THE ASSEMBLY AREA FOR THE GENERAL POPULATION GATHERED IN TO CELEBRATE MID-WINTER.

The top of the ridge running SSW (red arrow) for almost 200 metres and encompassing the sighting pit position, is a wide, flat plateau, very suitable for an assembly area. It would also have served the community well for gardening or a village, although there is no stream and water would likely have been hauled to the plateau in calabashes.

The high ground in the vicinity of the sighting pit is wide and flat, suitable for an assembly area.

Light filters through the canopy and the walk through was fairly easy, except where there were tangles of steeplejack vines.

The plateau remained consistently flat and it was probably partially excavated across its width and length to be so many centuries ago.

A view out to the east, offering a glimpse onto part of Pirongia Mountain. Here the ground drops away down into the Bridal Veil Falls valley.

From the sighting pit, the highest peak of Mount Pirongia represented the outer-marker for the summer solstice sunrise.

Refined calculations are yet to be made, but from the Waireinga (Bridal Veil Falls) hilltop observatory the summer solstice sunrise should be at or very close to the highest peak of Mount Pirongia.

AMPHITHEATRES & OTHER SIGHTING PITS AT WAIREINGA.

Reverend Richard Taylor wrote the following about the Patu-paiarehe:

'They are seldom seen alone, but generally in large numbers; they are loud speakers and delight in playing the putorino (flute); they are said to nurse their children in their arms, the same as Europeans and not carry them in the Maori style, on the back or hip. Their faces are papatea, not tattooed, and in this respect also, they resemble Europeans. They hold long councils, and sing very loud; they often go and sit in cultivation's, which are completely filled with them, so as to be frequently mistaken for a war party; but they never hurt the ground…

The belief in the Patu-paiarehe is very general; many have affirmed to me that they have repeatedly met with them. Albinos are said to be their offspring, and they are accused of frequently surprising women in the bush.' (see Articles from "Te Ika A Maui, NZ and its Inhabitants", by Rev Richard Taylor, written in 1855; facsimile reprint in 1974 A.H. & A.W. Reed).

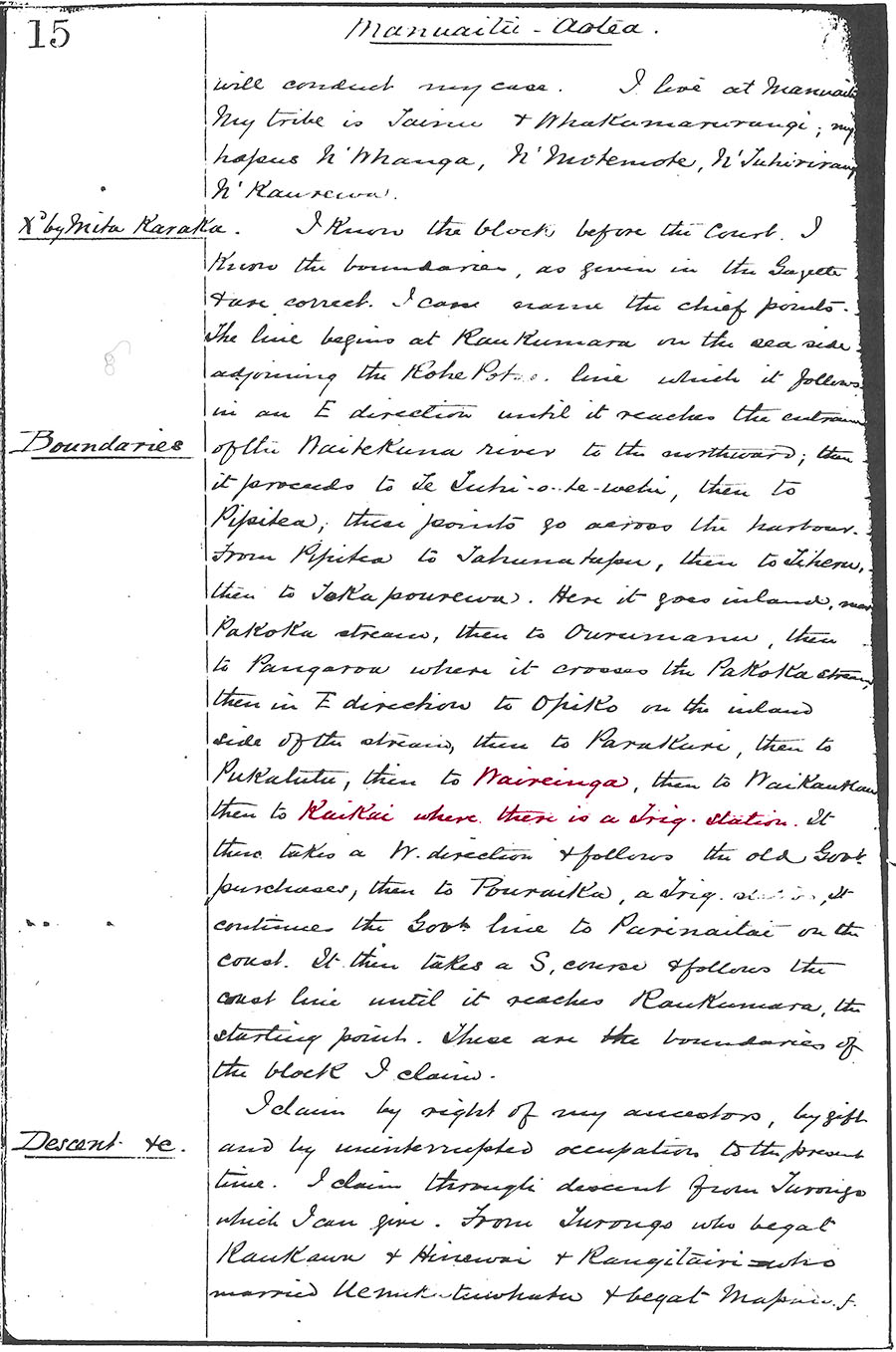

In the 1887 Maori Land Court Minute books the above arrowed-hillock shown, part of the Waireinga Reserve, is listed as a "trig" and boundary marker between Maori tribal territories and is considered to have been a Pa habitation centre for a community. The evidence suggests that it had, long-ago, most certainly been a centre for the Patu-paiarehe people at remote epochs, but had long-since lain vacated and abandoned by 1887. Evidence that it had been a Patu-paiarehe living location is substantiated by the following:

(1). Maori oral traditions and history.

(2). The clear cut evidence that solar observatories, for fixes onto the winter & summer solstice sunrises and sunsets, had been built there.

(3). Evidence of amphitheatres for entertainment, oratory and counsels. The Patu-paiarehe are renown for gathering together in large numbers in cultivations and singing or speaking very loudly. In most centres where they dwelt in large numbers across New Zealand, there will invariably be found bowl-like amphitheatres, either semi-natural or laboriously built.

Waikato Maori Land Court Minute Book, Volume 16, pg. 15. Courtesy of Hamilton City Libraries.

Down in the larger of the two amphitheatres are 3 additional sighting pits in a line, but separated from each other by about 30-feet (9-metres). The two shown in the above picture orientate towards Mount Karioi and would have worked well as solar observatory viewing platforms. In this case, however, the winter solstice sun would be observed to alight onto the higher southern peak of Mount Karioi, rather than skimming the more northern, slightly lower, peak and settling into the centre trough of the mountain. The third sighting pit mentioned had no sight-line onto Karioi Mountain, but targeted a coastal Pa settlement to the south of the mountain.

And so, yet another ancient Patu-paiarehe solar observatory, lost from memory for centuries, emerges back into historical recognition to, once again, provide a very accurate fix onto the exact day of the winter solstice.

Martin Doutré, 24th of June, 2023 ©